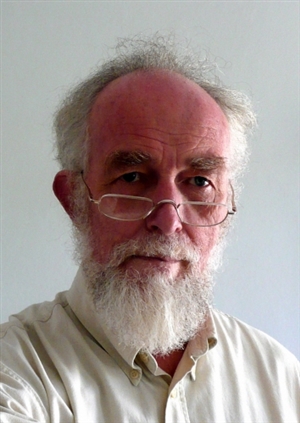

‘Strategic National Cybersecurity’ by Prof. Martyn Thomas

“It is widely accepted that cybersecurity is a large and growing problem, but companies and countries do not behave as if they really believe it. Systems cannot be safe if they are not secure.

If cybercrime were a disease, we would describe it as a pandemic and mobilize international resources to eradicate it at its root. Instead we merely advise the adoption of better hygiene, treat major outbreaks when we have to, and accept the rest of the damage as part of the rent we pay for living in a cyber-enabled world.

This is not sustainable. The problems we face with the systems that we currently have installed are just the beginning. Cybercrime is too easy to commit and too difficult to detect, disrupt and prosecute. Where there is money to be made, we always find unscrupulous, greedy and criminal behavior. Already, hospitals have been attacked with ransomware and paid the ransom, but there are millions of other potential victims and many ways to attack them. We have a legacy of vulnerable systems throughout our businesses, our infrastructure and our homes. We have built a society that depends on computer systems for defence, healthcare, leisure, manufacturing, transport and commerce, and most of these systems were designed and built before the threats from buffer overflows, injection attacks and other vulnerabilities were widely recognized.

These widespread vulnerabilities undermine national strategies. Cyberspace is not geographic, so we cannot defend Britain at our borders, nor can we continue to project military power overseas if our national infrastructure (both “critical” and less critical) can be disrupted or disabled in response. What would be the use of an aircraft carrier against an adversary that has demonstrated the power to disable our hospitals, GPS receivers, or network routers? What will we do when terrorists make determined use of cyber-attacks?

The number of vulnerable systems grows every week and will continue to do so. We want the benefits of the Internet of Things, driverless cars, robots, intelligent control of our homes, and information and entertainment instantly and everywhere. We value features and convenience above safety and security and so that is what we are offered and that is what we buy. Cybersecurity strategy cannot be divorced from industrial strategy and remain credible.

Current cybersecurity strategies are inadequate against current and future threats because they are largely based around two fallacies.

The first fallacy is the belief that you can show that a system is adequately secure by testing it and fixing the vulnerabilities that you find. Testing is by far the main way that software developers currently decide that their software is fit for purpose, even though we have known for decades that the vast majority of system states will remain untested even after months of running tests. Penetration Testing suffers from the same problem. As a way to ensure cybersecurity, testing is a category error.

The second fallacy is that computer users can be persuaded or trained to behave completely securely if to do so would be inconvenient at best and might even be impractical. When emails have attachments and embedded links, people will open the attachments and follow the links. If we design systems to be used in a particular way and then tell the users of those systems to follow inconvenient advice that they shouldn’t use the facilities that we have provided, we know that the advice will be ignored by some users.

Current cybersecurity strategies are really only short-term tactics to limit the damage. A strategy worthy of the name must aim to create a future where the security of software-based systems can be guaranteed and where assurance is based on scientific principles that are as strong as those we expect to be used for other important engineering products.

I shall suggest how this might be achieved”.